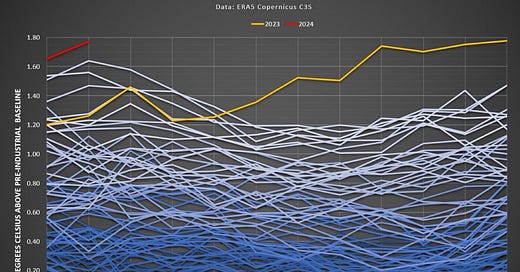

February 2024 was the warmest February on record in the Copernicus ERA5 dataset. Yesterday, climate scientist Zeke Hausfather announced this on Twitter/X. At 1,79 °C above preindustrial temperatures, it beat the 2016 record, measured -as this year- in an El Niño year.

If it feels like old news that a monthly climate record is broken, I understand the confusion since we have heard this every month since June last year. The El Niño event is partly to blame, but human-induced climate change is the structural contributing factor. You will likely hear this news a few more times in the next week when different institutions have analyzed their data.

Quite a few of these institutions will write about the temperature anomalies in central and (south)eastern Europe. Wiener Neustadt in Austria measured its warmest month of March in 1949; however, this year's February temperatures broke that March record. This winter was the warmest since temperature measurements have been recorded for Austria. Last month, it was 7.5 °C warmer than average in southeast Poland.

There was more climate news, for instance, about increasing rainfall in the Arctic. Information from this region, which warms three times as fast as the planet's average warming, may not sound relevant to those far away from that cold, barren, and beautiful region. Yet, climatic changes far up in the cold north will impact all of us.

In the coming decades, melting sea ice and more open water will lead to an increase of up to 60 percent more precipitation. Many places will see more rainfall than snow, altering the Arctic significantly and contributing to rising sea levels.

These rain-on-snow events result in more flooding, thawing permafrost, landslides, and new challenges for the animals and indigenous peoples that live in the Arctic. Rain hardens the snow, which makes it impossible for reindeer to reach the plants beneath the snow that they need to survive the harsh winter conditions. In a recent article in YaleEnvironment360, Ed Struzik mentions how the caribou numbers plummeted in Canada's central Arctic. The numbers of the Bathurst herd dropped from roughly 470,000 animals some 40 years ago to just 6,240 animals today.

As so often in my life, I learn in media, studies, or conferences about ecosystems collapsing in my lifetime while still enjoying beauty in the bubble that I live in. It is not that I don't experience changes myself; for instance, I have noted the disappearance of butterflies, many other insects, and certain bird species in my country. But these go so slowly that I risk changing my baseline during my lifetime. I need specific memories, like that summer when I was trying to count the butterflies in my parents' garden as a child, to remember the changes I experienced.

I only realized that I no longer needed to clean the car's windshield and headlights from insects when somebody reminded me of the grey haze of dead bugs that blocked our views in the 1970s and '80s. The next generation will start at another baseline, which may be that you sometimes see a beautiful butterfly in summer. It's a fraction of the numbers I grew up with in my parents' garden, but likely, my memories of hundreds of butterflies pale by those of my parents or grandparents.

It's too early in the season to see butterflies in Zeeland, but I do experience other changes. Although less extreme as the rainfall increases in the Arctic, the annual precipitation grew in the Netherlands by 26% between 1910 and 2022. We experience especially more rain in the winter. However, the number of rainy days has mostly stayed the same, which explains why the precipitation has become heavier in winter and during summer downpours.

To illustrate, the recent weather on my island has been very wet; I even had to change some of my popular walking routes because the ground is too wet to walk on. So, on this dry day, after days of rain, I visited one of the islands to the south to continue one of the long-distance walks I'm following, which roughly tracks the Dutch coastline.

I should have known better. This photo is not the reflection of a tree in a lake, but it is the path I was supposed to follow. In the middle of the picture, you can see how this walk continues from one huge puddle into the next. My worn-out summer-type Camino hiking shoes were no match for this challenge, and I adjusted my route to a slightly dryer track that led me to a sludgy path on higher ground. I enjoyed walking the much dryer dunes in the afternoon under bright blue skies.

It was rainy but also much warmer than it should have been in this season. The Netherlands broke the all-time record for the hottest month of February. It was 8.2°C, smashing the 1990 record of 7.6°C. It was a wet month, too; last month ranks fifth of all Dutch Februaries with the most precipitation.

We're not the only ones breaking records. Data from the World Meteorological Organization show that parts of North and South America, northwest and southeast Africa, southeast and far eastern Asia, western Australia, and Europe all saw record-breaking temperatures daily or for the entire month.

According to preliminary estimates, much of Europe (except for the north) had a February average temperature of at least 2°C warmer than usual. Some parts of central and southeastern Europe have even higher deviations from normal at 4–6 °C.

Many temperature records were also broken in the US, where the highest temperature was recorded in Killeen/Fort Hood in Texas at 100 °F (37.8 °C). Wildfires swept across the Texas Panhandle, with the Smokehouse Creek fire described as the second largest in the history of Texas. As a reminder, we don't discuss a dry, hot wildfire season in late summer; it is February. The wildfire hit a cold front east of Amarillo, resulting in snowflakes falling into the flames.

Yesterday, John Vaillant described this event in the New York Times and reflected on our times and the climatic phase shift we experience:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Planet 🌎 to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.