NASA has updated its well-known climate spiral visualization by adding 2022; the spiral keeps growing and getting dark red, indicating a warming planet. It made me wonder how I experienced climate change in my lifetime. And you may ask yourself that question too.

Have a look at this short YouTube video, and watch until the end to see the 3D version.

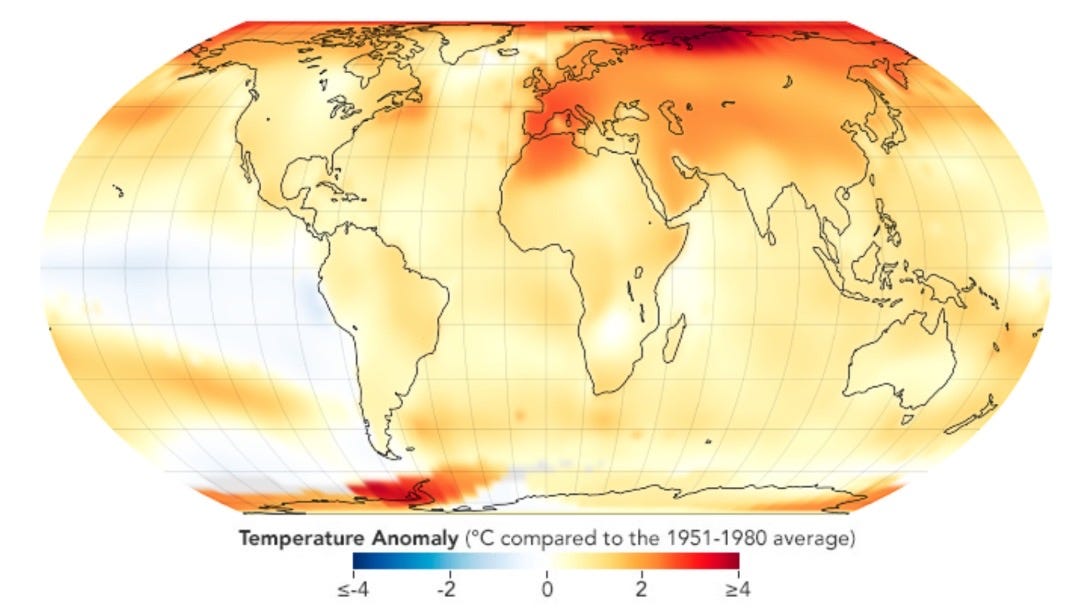

You will likely have seen earlier versions; the visualization shows monthly global temperature anomalies in degrees Celsius between 1880 and 2022. Temperature anomalies are deviations from a long-term global average. In this case, the period 1951-1980 is used to define the baseline for the anomaly.

As the years count up, the line spirals through the months of the year and around the circle. It turns to blue hues when temperatures are below average and red and orange hues when temperatures are above average. As the spiral progresses, the lines form a deformed circle that becomes predominantly more red, indicating Earth's warming up to more than 1.1 degrees Celsius above average.

1980s: optimism

The last flip of the image gives an exciting and frighteningly new perspective of the expanding collum. It has made the change in our climate since the early 1980s much more visible. You may remember it as the decade that we (rightly) feared dangers like nuclear destruction and AIDS but were not yet worried about the existential threat of the slowly but surely rising temperatures of our oceans and atmosphere. For me, these were my student days in Utrecht, the Netherlands; I mostly recall the optimism of those days and a belief in constant progress, especially in the second half of that decennium.

1998: the global perspective

A decade later, in 1998, I worked on environmental issues during a short diplomatic posting in Bonn in the last days before our embassy moved to Berlin. Our primary focus was regional environmental challenges like acid rain or bilateral issues on rivers, pollution, or even as local as noise from an airfield across the border. It is not that we completely ignored the global perspective; the leading worldwide environmental problem that received attention was the ozone layer's destruction. The good news was that countries had agreed on a solution.

While I was in Bonn, there was a preparatory meeting for a COP on another global challenge: climate change. The activity fell under the then still young and hopeful UN climate change treaty, the UNFCCC. The Kyoto Protocol had just been adopted, but it would take another seven years before it entered into force.

I remember it triggered me to get more interested in climate change in those days and reading reports about it during long evenings in my small furnished rental apartment in Bad Godesberg. I still feel that place's dated and kitschy vibe, especially the excessive use of dark oak wood that dominated every corner of the living space. Removing the hideous carpet from the bulky dining table did little to reduce the ugliness since the tacky copper lamp still hung above it. The central painting on the wall resembled the unique genre of the sad little boy with a tear on his cheek.

For a few months, I lived in this uninviting place, and it was there that I read all I could find about climate change. When I returned to The Hague just before Christmas, I was convinced of the severe threat that climate change posed. And rightly so; you can see how NASA's graph expands in this period. However, I don't recall being struck with the sense of urgency as I feel it now. It's not that the studies weren't unequivocal that we shouldn't waste any time and that the best window of opportunity to change course was now. But it felt different than today since I didn't see climate change's impacts in my daily life.

Looking back, I found it hard to imagine the sheer scale of the climate change impact that was about to take place worldwide. For example, the famous ice skating "eleven cities tour" could only be organized during harsh winters in the Netherlands. And the year before, we still enjoyed this most significant sports event in the Netherlands. It's an ice skating race that measures about 220 kilometers (135 miles) on the canals connecting the eleven cities in the Friesland province of the Netherlands. Why should we worry if it still gets that cold? I realize now that it would be the last time there was enough ice on the Dutch lakes to organize it. A wake-up call similar to my recent experience in Ottawa, where for the first time, the famous world's biggest skating rink couldn't open because of a lack of ice. I didn't expect to ever write that the winter in Ottawa isn't cold enough.

2006: An Inconvenient Truth

Fast forward another decade, and we were all watching Al Gore's documentary 'An Inconvenient Truth,' it was nearly a decade after those early days in Bonn. It was also after the Kyoto protocol but still before the failed climate summit of Copenhagen. In the video, you can see that the spiral was undeniably starting to spin out of control. However, this was also when most of the media still didn't get it and fell for the confusion created by the fossil fuel industry.

I lived in Vienna, in a bright apartment with my own furniture. I got my first internet connection at home, drilling holes through the walls for the cables in the pre-wifi days and hearing daily the dial-in sounds of my modem. The primary source for news was still printed media and television, and I remember how the world's top news channels were doing their utmost to be 'balanced' in their reporting. This meant, for instance, that the presentation of a deeply worrying report by the chairman of the IPCC, representing the peer-reviewed science of the world's best climate scientists, got just as many seconds on the evening news as a self-declared expert who expressed the 'other opinion' and sold nonsense to the world's television audiences with self-drawn graphs and cherry-picked data.

During my years in Vienna, I focused on the impact of climate change. I remember the presentations in the Hofburg, once the palace of the emperors of Austria, and our discussions about how a changing climate would impact security in Europe. Every Thursday morning, I enjoyed breakfast with some EU colleagues in the historic Cafe Central, where we speculated about increasing drought and extreme weather. But it was still an incomplete patchwork of worries; we missed many interconnections and didn't expect much change in our lifetimes.

Looking back, the scientist's predictions proved surprisingly accurate on the rise of atmospheric temperatures. Still, it seems even the best experts had not expected the system to be so dynamic that dramatic changes would already occur at the scale that we witness now.

2023: Finally, many feel a genuine concern about climate change

And now, we are in 2023. NASA has just added the latest data for 2022. As you can see in the ever-expanding and increasingly red spiral: the past eight years were the warmest eight years ever measured on the planet. What has changed compared to previous decades is that many people have finally accepted climate change as something to be concerned about.

For example, a Yale Program on Climate Change Communication poll in 2022 concluded that 51% of Americans believe global warming will harm their families. Still shockingly low, but it seems reality starts to sink in. And in the past few years, I noticed that my friends now finally talk about climate change, which is easy to understand since you must be blind not to recognize nature's changes around you.

In my talks and writings, I noticed that I shifted this decade from referring to scientific reports to telling about my own experiences. I hope this makes it easier to recognize the changes we all see in our lives. And I spend much more time nowadays sharing the stories of the beauty we still have. For example, I write about being in nature and tell others how much I enjoy hiking and photographing the beauty of the natural world.

The details are often still there to be enjoyed. Think of finding the first blossoming flower after the winter, which is still as stunning as before. But zooming out to the bigger picture has become painful, and NASA's spiral shows the extended time frame and the global scale; it hurts to see our planet's, and thus our future's, destruction mapped so clearly.

This newsletter is part of that effort of storytelling. I hope it helps you to see our world differently. This small, crowded planet is more vulnerable than you may realize. Yet, it is probably much more beautiful than most acknowledge. So two ways of viewing our world go hand in hand: appreciate our planet's beauty and thus be more motivated to preserve our precious home.

That's why this newsletter is called The Planet.

If you got this far, please read this too:

I write this newsletter because I believe that together we can do better on this beautiful but fragile planet.

Please consider supporting this initiative by taking a paid subscription.

Notes:

I am fascinated at how human history seems to "balance on a knife edge from time to time" with tipping points that seem unrelated at the time. What if the electoral process in Florida had not depended on whether to count "votes on computer cards with hanging chads" and Al Gore had become president instead of George Bush in the year 2000 ?

Would he have started the de-carbonizing process in time to prevent our present spiral into climate crisis?

We certainly would have stood a better chance to begin significant remediation sooner.

A very powerful issue today. This one struck a cord with me more than most, as I vividly recall witnessing the Elfstedentocht in 1997. The excitement that our friends who skated it and those of us who were spectators felt was palpable, and it saddens me that it is very unlikely to occur again in the foreseeable future. But I still take joy in the beauty that surrounds me on a daily basis, and I truly appreciate your regular reminders- both to take note of the beauty and to act more responsibly on behalf of our fellow inhabitants of Planet Earth. Thank you.