The impressive structure on the left is the Mauritshuis, which translates to Maurits's house. The famous museum in The Hague derives its name from the man who commissioned the building and was its first owner: Johan Maurits, Count of Nassau-Siegen (1604-1679). Since its official opening as a museum in 1822, the Mauritshuis has become renowned for its impressive collection of Dutch Golden Age paintings, including masterpieces by Vermeer, such as the instantly recognizable Girl With a Pearl Earring.

I passed this spot earlier this week in The Hague while walking on the slight elevation known as the "Vijverberg," a name that roughly translates as the mountain next to the pond. I enjoyed the view with its symmetry, beauty, and historic connection, so I stopped, took one shot, and walked on. As a lifelong photographer with a passion for history and nature, I often view the world through these lenses. All three perspectives blended in this picture in a beautiful play of lines, contrast, and color.

It is easy to portray this image as one of preservation and continuity. Our ancestors who walked here saw more or less the same as we see now. So let's start a journey and transform the image into a sepia-toned sketch that looks more historic:

Does this sketch reflect what the citizens of The Hague might have seen centuries ago? I removed some modern structures on the left and roughly altered the modern-looking backpack of the second person from the right. With more time, I might have added period-appropriate hats, but these details are minor compared to the broader changes in high-rise architecture and fashion.

But besides architecture and fashion, what else has changed in this seemingly timeless view?

For one, technology has changed. Two hundred years ago, a painter would have worked weeks or longer to create such an image. A century ago, a photographer needed hours to capture, develop, and print a photo. Today, with my iPhone, it took merely a fraction of a second, with no additional costs for materials.

Societal norms have also transformed. The concept of leisure time and travel has shifted radically over the past century. While Sundays were traditionally reserved for church and family, the notion of paid holidays to explore places like The Hague and sit on the pond's edge like these four tourists was unimaginable for most people in previous centuries.

Democracy has changed. Most buildings to the right of the Mauritshuis are parliamentary buildings. You can see the Senate on this side, while the lower house of parliament meets in a more modern building connected to the same complex known as the Binnenhof (the Inner Court). It wasn't until 1919 that women gained the right to vote in the Netherlands. Democracy isn't fixed; it develops over time, which is part of its strength. At the same time, we shouldn't forget that democracy is not a stable end situation for human development; it needs protection against those who want to replace it with an authoritarian government.

And finally, history itself changes through history. I learned at school that the Mauritshuis was built in the Golden Century, but nowadays, the museum is careful not to use these worlds anymore and uses the more neutral form of the 17th century. It may have been a golden time for a man like Maurits, but it wasn't for the vast majority of people and certainly not for the enslaved people in overseas colonies.

When I was at school, we learned about the slave trade, including the Dutch role, but I never knew of Maurits' role in the slave trade until I read a critical article about him about a decade ago. Nor did I fully realize how long enslavement was still in practice in the 19th century, long after the slave trade had been abolished. The 17th century felt like a long distant past, but well-documented mid-19th century human rights abuses by the Dutch feel uncomfortably recent.

I learned more about these aspects of our history last year at the UN headquarters in NYC; the Netherlands government had organized a public exposition at a central location in the building about the Netherlands' involvement in the slave trade. I also learned more about our history in the Mauritshuis, where the museum explains its historical connection in its exhibitions, including how painters depicted enslaved people in some of the 17th-century paintings in the museum.

So, on closer inspection, the photo and the semi-historic sketch depict far more than an image of historical stability; there is always more than meets the eye.

Let's take this exploration of change one step further: even the photo composition carries a time stamp. In many historical periods, a central tree would not split the image into two parts, as you see here, except for some religious themes in art. It would have been more acceptable in 18th and 19th-century Japanese art and through its influence in late 19th-century European paintings.

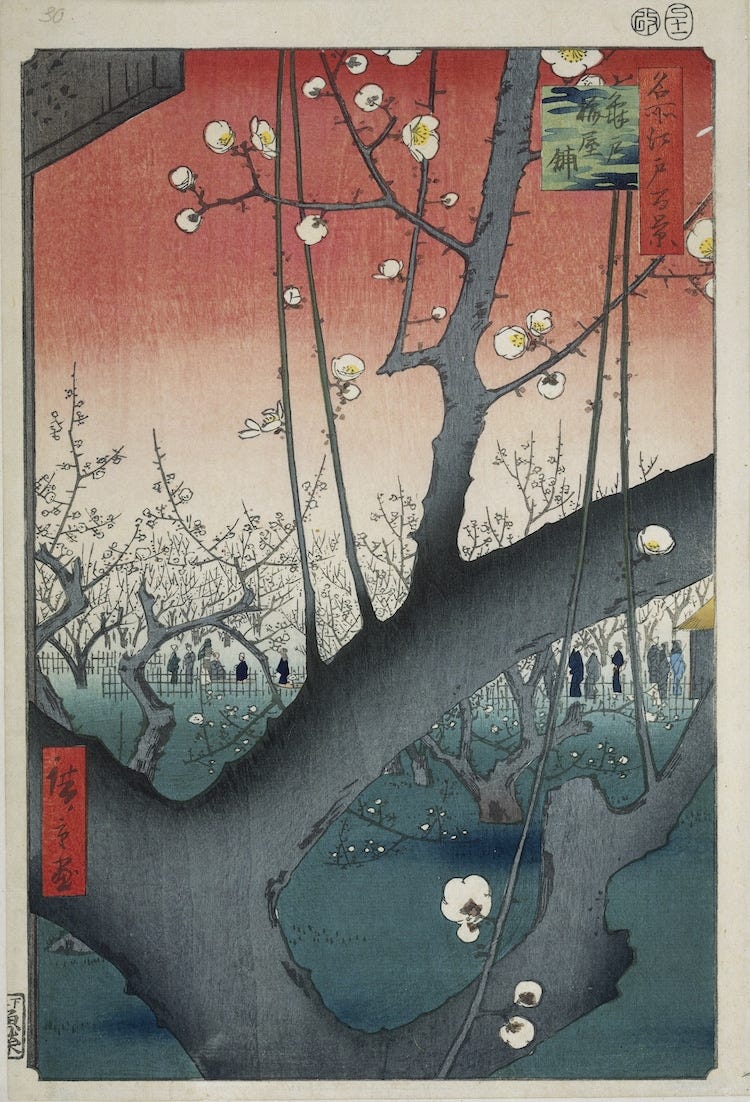

You will likely recognize this famous woodblock print, created in 1857 by Andō Hiroshige. It is known as "The Plum Garden in Kameido" (also known as "Plum Park in Kameido"). Note Hiroshige's use of a unique perspective, with the thick, grey branches of the plum trees dominating the foreground.

This print influenced Western artists, including Vincent van Gogh, who wrote that Japanese art made him happy and cheerful. He created his own version titled "Flowering Plum Tree (after Hiroshige) in 1887. Van Gogh's use of colors is more intense, and he replaced the black and grey tones of Hiroshige's tree trunk with vibrant red and blue hues.

Japanese art, especially prints known as ukiyo-e, also inspired Paul Gaugin. Flat areas of color, bold outlines, and intense compositions influence his works. Five years after his (one-time) friend Van Gogh had painted his version of Hiroshige's tree, Gaugin painted Mata Mua (In Olden Times). It depicts an idyllic scene with Tahitian women worshipping the goddess Hina, playing music, and dancing. This painting brings us back to the composition with a central tree, which divides the composition and is reminiscent of Japanese art.

Moving from the Pacific islands back to the spot in The Hague, where I stopped earlier this week for a mere second to take this picture, I want to mention one more local but world-famous painter: Piet Mondriaan. I believe that Mondriaan must have walked at this spot, which is hard to miss for anyone who lives in The Hague. He would have appreciated this composition since distilling the verticals and horizontals is straightforward from this viewpoint.

Mondriaan found a lot of his inspiration in the summers on the islands of Zeeland. And with that, I end my train of thoughts on an island just north of the one he preferred to visit. I type these last words near the island's western tip in the setting sun on a late summer evening, and every tree I see now has a different role in the composition of the landscape.

Did you know that clicking on the ❤️ at the bottom or the top of this post will help others discover my publication? You can also share it with others. The best way to support my work and not miss anything is by subscribing to this newsletter.

There is often something extra to enjoy on Patreon:

Or perhaps you liked the article and want to support my writing by buying me a coffee?

I always love to read subscribers’ comments:

How D-Day Caissons Saved an Island

Following the D-Day invasion on June 6, 1944, the Allies faced the daunting task of landing troops and supplies on the French coast. With existing harbors either occupied by Germans or at risk of destruction, temporary harbors, known as Mulberry Harbors, were urgently needed. Central to this effort were the Phoenix caissons—massive floating concrete units constructed in England and transported across the Channel to Normandy.

My Mother was born in 1916, & that was before women had the right to vote here in the States. I hope to see a woman President this November. The Equal Rights Amendment, first proposed in 1923, would guarantee equal legal rights to all American citizens regardless of sex. It has never passed in Congress. That speaks volumes.

I always enjoy & learn from your photos and writings. Thank you for sharing.

Historical context. History and art lesson. Democracy. Brilliant 🌻