"The ice-bridge jam gave way last night, and the river was passable only in canoes; the banks were piled with rough ice, and fields of icebergs were floating down the river... It was a most thrilling experience."

In early 1902 the fourth earl of Minto, who was the eighth governor-general of Canada, used these words to describe his crossing of the Ottawa river to Quebec. His wife, the Countess of Minto, joined him on this trip. To my surprise, I found that the Library of Congress has a two-minute video of this event. You can watch it here. I noted the amount of ice. My Canadian friends seem to be correct; this was a mild winter.

Lord Minto actively promoted heritage preservation, and his efforts led to the creation of the National Archives of Canada. I suppose that he would therefore be pleased to know that the modern bridge built around that time in Ottawa and named after him is now a well-known heritage bridge.

Today, I passed the Minto bridges; it is a set of three. Now that practically all the ice is gone, I enjoyed their reflections in the water.

After all these months, it is nice to get to know Ottawa without the snow and ice. Watching it disappear is even more fascinating than seeing all that snow come down a couple of months ago. But ice-melting in the more remote areas of the Planet profoundly worries me. Have a look at this 35-second video in a tweet from Kris Karnauskas, who leads the Oceans and Climate Lab at the University of Colorado in Boulder.

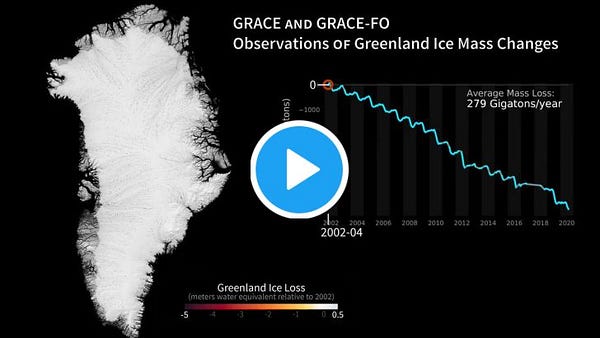

Climate change leads to surface melting and iceberg calving in Greenland. In the past 18 years, this enormous island lost so much ice that the global sea level rose 0.03 inches (0,8 millimeters) per year. I don't think this is a convincing number to keep you awake tonight, nor is that the aim of this newsletter. But all melting of ice-sheets, including Antarctica, add up, year after year.

While the climate change drama has astounding speed in geological terms, its pace is far too slow to worry policymakers. We live our lives in less than a century, and therefore our imagination is incapable of seeing any further than that period. Perhaps some think of their children and expand their vision with a few decades. The end of the century is about as far in the future as we are prepared to talk about. Flip those 79 years back into history, and you find yourself in 1942. That doesn't sound that far. We still deal with the horrors of that time. Or in a more positive formulation: we still enjoy the results of the Second World War's major turning points that all happened in that year.

Expanding water

A critical discovery that contributed to the industrial revolution was the steam machine. It was based on the principle that water expands when you heat it, and then you can use that energy for all kinds of processes. From the earliest days after this discovery, a favorite steam energy use was pumping water out of the coal mines. The coal was then burned to heat even more steam machines or facilitate other production processes. In the last century, we enthusiastically added other fossils fuels to burn, like oil and gas.

We burned so much that we finally heated the atmosphere, not directly like you heat the steam machine's kettle, but because of the produced greenhouse gasses. More than 90 percent of the energy that is thus trapped is absorbed into the oceans. And that brings me back to where we just started: the same principle that got us into this mess, the expansion of water, is now coming after us with an act of revenge. The oceans also expand once they get heated. So we have to deal with a double-whammy of melting land ice and the expansion of warmer oceans. Predictions of sea-level rise at the end of this century are difficult to make since we don't know what climate policies our leaders will pursue. But a meter (or more if we keep ignoring the urgency) is well possible.

These worries of climate scientists (and anyone else who pays attention to the Planet) are not shared by all politicians. In the New York Times, you can read about Ron Johnson, a Republican Senator from Wisconsin. He blames "sun-spots" for climate change instead of the proven man-made causes. Nor is he worried because CO2 is good for trees. He also says that Greenland has a good reason to be called green because it was green at one point in time.

Greenland

The Planet's regular readers may remember the recent ice-core study that revealed that a million years ago, or perhaps 400,000 years ago, there was a tundra landscape in northern Greenland. But that was long before the emergence of us, the Homo sapiens sapiens, on the Planet, some 200,000 years ago.

Greenland got its name in an early example of a clever marketing campaign. Erik the Red was, by all accounts, not a very pleasant man. About a thousand years ago, the Viking was exiled from Norway for killing people. Later he was expelled from Iceland for killing more people. The land he then sailed to had no people to kill (at least not in that southern part of Greenland, the Inuit were probably around this time, making their entry much farther to the north). He promoted the green valleys he found between the icy fjords and massive ice-shields as ‘the green land’ to lure settlers.

Some 400 years later, the community he had founded still lived there but then suddenly disappeared from history. The last things anyone heard from them are in a few early 15th century letters about a wedding and the burning at the stake of someone accused (and found guilty, I suppose) of witchcraft. Here is some fascinating reading about what may have happened to them.

We can easily relate to three main elements of the theory of the existential challenges they had to cope with:

changing trade relations

climate change

a major pandemic

History lessons should get a higher priority in education, especially for those students who have senatorial ambitions.

Dense and filling, this is a fascinating story about Vikings. Including charts, maps, short movies, and lots of pictures. What’s not to like? Thanks! 👏🏻👏🏻

Fascinating links to what may have happened to the Viking settlements in Greenland. Archaeologic links to climate,

mystery.....what’s not to love about this article?🕊️